Illness, Failure & Death

ILLNESS, DEATH & FAILURE: THE TELLTALE SIGNS OF BEWITCHMENT

Witchcraft: a source of evil

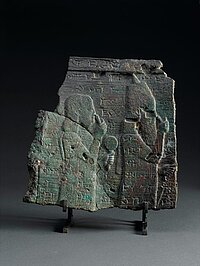

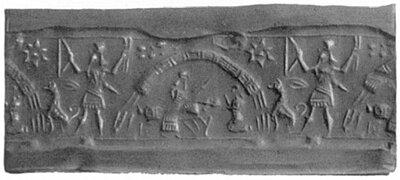

The conviction that ritual acts, prayers and incantations, food and drink, drugs and ointments can not only be used for a person’s benefit, but also with evil intent to harm people, is common to many, maybe even all cultures that take the effectiveness of symbolic acts somehow or other for granted. Mesopotamia is no exception to this rule, and witchcraft was considered by Babylonians and Assyrians to be one possible cause of illness and mishap.

Witchcraft-induced illnesses

While all witchcraft-induced sufferings could be referred to by the single term ‘hand-of-men’-disease (Akkadian qāt amēlūti), various different sets of symptoms could be diagnosed as witchcraft-induced. These include stomach problems, lung diseases, impotency, emotional problems, mental disorders and complex, serious diseases that caused severe pain, paralysis and a rapid deterioration of the patient’s health.

Nevertheless, the diagnosis of bewitchment was not arbitrary; certain signal symptoms like excessive salivating, bleeding from the mouth or the unusualness of the disease pattern were regarded as typical for witchcraft-induced ailments.

The variety of symptomologies corresponds to numerous differentiated witchcraft diagnoses among which one can distinguish two main groups:

- bewitchment caused by the performance of evil rituals, often involving the manipulation of substitute figurines representing the patient, and

- bewitchment caused by contact with bewitched substances.

Symptoms

The symptoms that were associated with bewitchment are known to us from so-called symptom descriptions that form part of many texts dealing with witchcraft-induced sufferings. These symptom descriptions are not referring to observations of one specific ill individual (case description), but rather offer a typical set of symptoms that indicates a witchcraft as the underlying cause of the patient’s suffering.

Diagnostic texts associate brief descriptions of symptoms with a diagnosis that provides either the name of the given illness or information on the cause of the illness (aetiology); diagnostic texts usually also offer prognoses on the further prospects of the patient and the treatability of his illness. Therapeutic texts detail instructions for the cure of specific illnesses or crises; they give directions either for the execution of a ritual or for the preparation and application of a medicine.

Victims of witchcraft

In principle anyone can become a victim of witchcraft, but most Babylonians and Assyrians went about their daily business without the constant fear of being bewitched; witchcraft belief became virulent only in situations of crisis, illness, insecurity and conflict.

Pregnant women and infants were regarded as potential victims, but most descriptions of sufferings diagnosed as induced by witchcraft give the impression that witchcraft affected first and foremost men, an observation that agrees well with the main stereotypes of the agents of witchcraft, the female witch and the male adversary in court.

The person of the king always deserved special protection; the texts of the Bīt rimki ritual in particular show that because of his many adversaries and enemies the king was regarded as a prime potential victim of witchcraft. One war ritual even accuses the foreign enemies of having tried to bewitch the king’s weapons and soldiers by wooing the favour of the Mesopotamian gods.

Sumerian and Akkadian texts are silent about bewitching whole villages, cities or countries; also animals, canals, wells, fields or orchards do not seem to be typical victims of witchcraft, though purification rituals for stables and agricultural areas are well known. This overall impression may to some degree be due to the fact that our main source of information on Mesopotamian witchcraft beliefs is a corpus of texts that, in modern terms, forms part of human medicine and focuses primarily on male elites. On the other hand, it seems hardly possible to dismiss the concentration of relevant sources in this segment of Babylonian technical literature as insignificant.

© Daniel Schwemer 2014 (CC BY-NC-ND license)