Maqlû

An extensive ceremony

The most extensive Babylonian anti-witchcraft ritual was called Maqlû “Burning.” Its performance stretched over one night and included the recitation of almost a hundred incantations. The basic pattern of the ritual is shared by most anti-witchcraft rituals and consists of a simple transition: the victim is transferred from a state of imminent death back to life, he is purified and his bound state undone; sorcerer and sorceress are assigned the fate they had intended for their victim by sending the witchcraft back to them. The reversion of the patient’s and the sorcerers’ fate is interpreted as a legal process that ends with the acquittal of the innocent patient whose unjustified verdict had been provoked by the sorcerers’ slander.

The opening section

The ritual Maqlû begins after sunset with an invocation of the stars, the astral manifestations of the gods. The patient allies himself with the gods of the netherworld whom he asks to imprison his witches and with the gods of heaven who are asked to purify him. The exorcist protects the crucible, which plays a central role in the following proceedings, with a magic circle, and the whole cosmos is asked to pause and support the patient’s cause.

Burning the witch

This is followed by a long series of burning rites during which various figurines representing warlock and witch are burned in the crucible. The following incantation is recited at this stage of the ritual. During the recitation of the incantation figurines of warlock and witch made of clay and tallow are put into the fire, where the clay figurine bursts and the tallow figurine melts (Maqlû VII 183–92, 200–203):

Whoever you are witch who took clay for my (figurine) from the river,

who buried figurines of me in the ‘dark house’,

who buried my water in a tomb,

who picked up scraps (discarded by) me from the dust-heaps,

who tore off the fringe (of a garment) of mine at the fuller’s house,

who gathered dirt (touched by) my feet from a threshold –

I sent to the gate of the quay: they bought me tallow for your (figurine).

I sent to the canal of the city: they pinched off clay for me for your (figurine).

I am sending against you the burning oven, the flaring Fire-god,

the ever alight Fire-god, the steady light of the gods,

…

She trusts in her artful witchcraft,

but I (trust) in the steady light of the Fire-god, the judge.

Fire-god, burn [her], Fire-god, incinerate her,

Fire-god, overpower her!

Deciding the witch’s fate; purification in the light of the rising sun

After the sorcerers’ death by fire has thus been enacted repeatedly, a figurine of the witch’s personal fate-goddess is defiled by pouring a black liquid over its head. By this act the witch’s evil fate, her death, is sealed, and the patient leaves her behind in the darkness of the night.

In the second half of the night destructive rites directed against the evildoers are more and more superseded by ritual segments that focus on the purification and future protection of the patient. The incantations greet the rising Sun-god as the patient’s saviour, and the ritual ends with the patient identifying himself with his own reflection in a bowl of pure water shimmering in the morning light.

Sources

The text of the incantations and ritual instructions of Maqlû was transmitted in Mesopotamia in the form of a series of nine tablets: eight tablets giving the full text of the incantations that were to be recited; one tablet giving brief instructions on the performance of the ritual and the actions that accompanied the recitation of the individual incantations. All anti-witchcraft incantations within Maqlû are composed in the Akkadian language, more precisely in the later literary form of Akkadian called ‘Standard Babylonian’.

It is uncertain when exactly Maqlû was composed. In the first millennium BC, the text of Maqlû had a fixed, ‘canonical’ form that is attested in many different libraries of Babylonia and Assyria. This canonical text probably goes back to a compilation, composition and redaction of the text in late second millennium Babylonia. The unknown scholar and exorcist who established the text of Maqlû certainly used older sources, and smaller collections of anti-witchcraft incantations that are known from Maqlû are already attested in earlier second millennium sources.

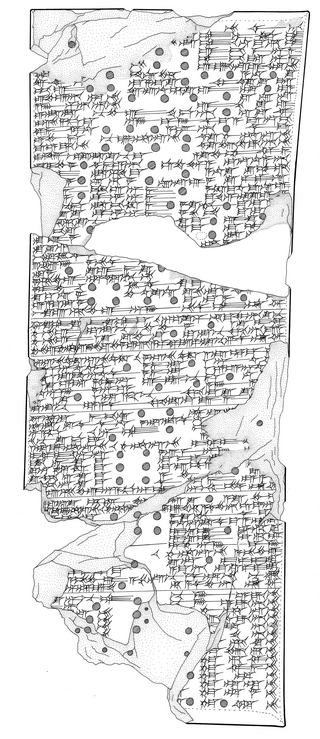

The text of Maqlû is attested in more than a hundred cuneiform tablets and fragments that were found in various libraries in Babylonia and Assyria. The most important group of manuscripts comes from the royal libraries of Nineveh (7th cent. BC), but also private libraries of exorcists, such as the library of Kiṣir-Aššur (Ashur, 7th cent. BC) and Iqīšâ (Uruk, 4th–3rd cent.) had tablets of Maqlû on their ‘shelves’. In the first millennium, Maqlû incantations formed part of the scribal curriculum, and many excerpts and copies of whole tablets prepared by students in the course of their education aid in the reconstruction of the text.

You can read a German translation of Maqlû here; you can also have a look at selected handcopies of cuneiform sources of Maqlû. A scholarly edition is being prepared by T. Abusch.

© Daniel Schwemer 2014