Blog

From 12th to 14th November 2025, the second MagEIA Symposium brought together scholars from a variety of disciplines to address the core questions raised in our call for papers. The meeting offered presentations that “threw stones in all directions” of our central theme: the interaction between materials and mechanics in magical practice, the procedures that activate them, and one of the questions at the heart of MagEIA, that of historical interactions and contacts and potentially universal solutions in the area of magic that have been observed repeatedly in different regions within our field of study.

Gideon Bohak’s discussion of the protective ritual of throwing stones in the four cardinal directions to protect a traveler set the tone for these explorations. Is this gesture a universal way of marking out safety, or does its wide distribution reflect the paths of travelers who carried it from region to region? Similar questions about recurrence and transmission resurfaced throughout the conference. In Gaby Abou Samra’s talk on Aramaic and Syriac magical texts, for example, we saw how concerns for thresholds and liminal spaces recur across traditions, and how objects such as magical bowls may incorporate elements from multiple cultural backgrounds, even invoking figures such as Jesus in contexts otherwise marked as Jewish.

Many contributions shed light on the mechanics of ritual procedures and the iconic or symbolic role of substances and objects. Chris Faraone demonstrated how inscribed rings operate through a combination of material contact and the agency attributed to the object itself. Panagiota Sarischouli’s analysis of recipes in the Greek Magical Papyri revealed how varying proportions of material handling, manipulation, and formulaic operations work together in procedures shaped by Egyptian backgrounds. Other speakers highlighted the iconic use of materials: for example, in a procedure designed to induce aversion and hatred, dung, hair and fresh flowers are mixed together. In Ethiopian tradition, colours also have a clear symbolic function. Celia Sánchez Natalías revisited the discussion about the practical and perhaps also symbolic use of lead in North African curse tablets, with the discussion prompting a comparison with Mesopotamian traditions in which lead symbolizes death or the defeated adversary.

The materiality of writing also emerged as a component of ritual mechanics. Sofía Torallas Tovar showed how different writing items may correspond to distinct ritual contexts and purposes, and several papers examined how objects and substances are believed to become effective. We heard about name magic involving writing the names of akh spirits on the neck of a mouse, making it immune to being caught by cats. Various papers also discussed the question of activation, both of texts – as Jon Beltz did for Akkadian – and of material – as Mersha Mengiste showed for the Ethiopic tradition, in which materials are usually thought to be active and activated by themselves – and of burial as the final step in activating materials, as Krisztina Hevesi pointed out.

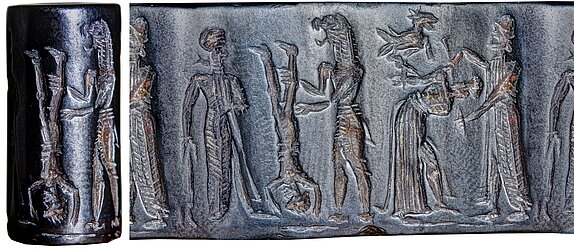

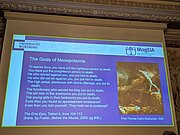

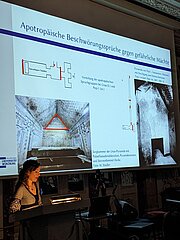

A further highlight was Daniel Schwemer’s keynote lecture on Mesopotamian apotropaic rituals, which focused on the key techniques and materials used by ritual specialists. Drawing on first-millennium BCE cuneiform sources, it examined how ritual materials and modelled representations were employed to counter harmful forces and support people in moments of crisis. The lecture showed how Mesopotamian experts sought to model and reshape a precarious world for the benefit of those in need, emphasizing the deep intertwining of mechanics and materiality in ritual thinking.

Overall, the papers of this year’s Symposium revealed how attentively ancient practitioners worked with the properties, symbolism, and operational potential of materials, and how these elements travel, transform, and reappear across cultures. These three days of conversation have opened new perspectives on the ways in which magic operates as a craft involving objects, substances, gestures, and interactions – and we look forward to pursuing these questions further.

‚Secret magical knowledge through the millennia‘

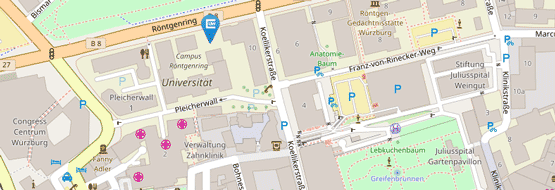

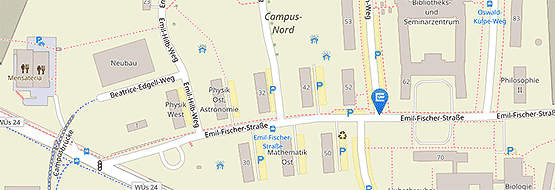

From September 8 to 12, the Deutscher Orientalistentag 2025 (https://www.dot2025.fau.de/), a huge congress for Ancient Near Eastern, Islamic and Asian Studies, took place at the University of Erlangen and Nuremberg in Erlangen. MagEIA-member Svenja Nagel participated in an interdisciplinary panel on „Magisches Geheimwissen durch Jahrtausende“, which was organized by Joachim F. Quack (University of Heidelberg, Egyptology). During this session on Wednesday morning (10 September), specialists from Egyptology, Ancient Near Eastern Studies and Islamic Studies discussed concepts of secrecy and exclusivity around magical knowledge and specific magical texts and rituals. With their respective fields of study, the panelists covered several cultural horizons and a timespan from the 3rd millennium BCE until the 15th century CE, thus being well in line with the scope of MagEIA’s own research focus.

The thematic panel started with two Egyptological contributions. Svenja Nagel (Würzburg) presented a paper on ‘“Neferkare kennt ihn, diesen Spruch des Re”. Magie und der Schutz Pharaos in den Pyramidentexten.’. On text examples from several spells inscribed in the royal pyramids of the late 3rd millennium BCE, she demonstrated that the deceased Pharaoh was explicitly connected to magic and the knowledge of magical spells in different ways, thus enabling him to acquire power, defeat enemies, and ascend to the sky as a most powerful god. However, although the position of Pharaoh was a special one, additional evidence from private tomb inscriptions shows that even in the Old Kingdom, certain types of access to magic and magical knowledge were also available to (high-ranking) non-royal people and especially, to priests.

This was neatly followed by the presentation by Joachim Quack (Heidelberg) on ‘Geheimes und öffentliches magisches Wissen im Alten Ägypten’, providing a diachronic overview of those types of rituals or specific texts that were available in some form to a wider public, or at least particular groups, versus those subject to stricter restrictions. Particular examples from more explicit sources demonstrate how such restrictions could be phrased and what could be the consequences of abuse of magical texts.

A change of scenery was set with the next contribution by Assyriologist Elyze Zomer (Tübingen) about ‘Was ich weiß, weißt du auch! – Geheimes Wissen in den Historiolae der altorientalischen Beschwörungsliteratur’. Zomer focused on colophons and a particular type of formula within Ancient Near Eastern exorcistic literature. In the 1st millennium BCE, special colophons explicitly designate the contents of some rituals as secret knowledge. As Zomer showed, many texts include dialogues between deities, especially between Marduk and Ea, that function as historiolae. They encode the transfer of knowledge from a higher god to his son, which probably reflects how ritual knowledge is passed on from a ritual expert to his student.

The final two papers dealt with Arabic ‘secret’ books on magic, which are strongly rooted in more ancient traditions and/or linked to other cultural spheres or languages and scripts, thus making them even more mysterious. Muhammad Husein Muhammadi Demneh (Tübingen) talked about a number of treatises from the Islamic world dealing with magical alphabets. His paper, entitled ‘Das magische Alphabet in der islamischen Tradition: Šauq al-mustahām, Durrat al-ġawwāṣ und Mabāhiğ al-aʿlām im Vergleich’, compared the details and information’s on the magical alphabets contained in the three named works, the first by Ibn Waḥšīya (4th or 10th c.), the second by the alchemist al-Ǧildakī (8th or 14th c.), and the third by al-Bisṭāmīs (middle of 15th c.). In the texts the alphabets are partly labelled as foreign scripts (e.g. as ‘Indian’) and their knowledge as secret. However, the alphabets differ from each other, and in turn from those used on actual amulets, thus preventing a decipherment of the latter with the help of these books. Demneh concluded that they foremostly served to credit the authors of the works with authority and special occult knowledge.

Finally, Bennet Alberth (Tübingen) presented the results of his recent MA-thesis in Islamic studies with a paper on ‘Die Planetendarstellungen im “Buch vom Nutzen der Steine und ihren Gravierungen” des ʿUṭārid al-Muḥāsib und ihre Vorlagen aus dem griechisch-römischen Ägypten’. Taking the section about Venus as an example, he traced back fascinating lines of traditions between this Arabic treatise from the 9th century and the gems and books on magical stones from antiquity, in particular from Graeco-Roman Egypt. On the other hand, ʿUṭārid al-Muḥāsib’s text formed the basis of a section in the great book of Arabic magic, Ġāyat al-Ḥakīm (‘The Goal of the Wise’), which in turn was translated into Latin under the name ‘Picatrix’.

The single papers and the whole session were followed by stimulating discussions between the panellists and the lively audience about magic and secrecy as well as shared or transmitted traditions of magic between different cultures, ancient and modern. A publication of the contributions (and perhaps additional ones) to this panel is envisaged.

From July 7 to 11, 2025, scholars from around the world gathered in Prague for the 70th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale (RAI), under the theme “From Cradle to Grave: Everyday Life in the Ancient Near East.” Among the many highlights of RAI 70 in Prague there was Workshop 07, Current Research on Mesopotamian Magic, organized by Nicholas Gill and Genevieve Le Ban. Papers covered a wide range of topics, including early witchcraft in the 3rd millennium BCE, poetic structure in love incantations, demon-banishing rituals, and comparative perspectives on magic in Mesopotamian and Greek traditions.

Many speakers are or have been affiliated to MagEIA: Nicholas Gill, Daniel Schwemer, Frank Simons, Beatrice Baragli, Jon Beltz, Marie Barkowsky.

Magic in Mesopotamia is not merely a sideline or exotic fringe of the culture — it often overlaps with core religious, medical, and social practices. Incantations, exorcisms, protective rituals, and demonological texts form part of what ancient practitioners and thinkers considered integral to maintaining health, averting misfortune, and negotiating human and divine agency. The textual and material record is rich, but many questions remain: How did magical practice evolve over time? What theoretical models best capture its performative dimension? How did ritual specialists present themselves in relation to divine authority? How were magical texts composed, transmitted, and used in daily and courtly contexts?

Workshop W07 addressed these questions, demonstrating that MagEIA currently serves as a central node for the study of magic within Assyriology.

On Tuesday, July 29, the MagEIA team undertook a day trip to bring the summer term to a close in a convivial atmosphere. In the morning we visited the Jewish Center Shalom Europa in Würzburg, a cultural center of the local Jewish community. It includes a synagogue and a museum with exhibitions on Jewish culture, religion and the history of Jews in the region of Franconia. During a guided tour we learned about the artefacts on display as well as the history of Jewish life in Würzburg. Most notably, the museum preserves nearly 1,500 Jewish inscribed tombstones dating to the period between 1147 and 1346. We concluded the tour with a visit to the synagogue inside the center.

At around midday, we began the second part of our excursion with a boat trip up the Main River to Veitshöchheim in sunny weather. We enjoyed the views from the upper deck while having lunch or a slice of cake on board. Upon arrival in the village, our group was free to explore the beautiful Rococo gardens belonging to the Summer Palace (Schloss) of the Prince-Bishops of Würzburg. Thus refreshed, we met again at the Jewish Cultural Museum of Veitshöchheim, where we were given a guided tour of the reconstructed synagogue, as well as the exhibition rooms in the adjacent Jewish residential building and mikvah from the 18th century. The exhibition is organized around the numerous genizah finds discovered in the synagogue’s attic in 1986 and subsequently studied, sorted and organized for the exhibition. They include books and various types of documents written in Hebrew and Yiddish. Apart from these fascinating objects, the exhibition provides valuable information on Jewish social and religious life as well as the history of local Jews, and more specifically, the personal life stories of former Jewish inhabitants of Veitshöchheim, some of whom escaped deportation and emigrated to the USA.

After a day of visits and absorbing lots of interesting information, we cooled down with some ice cream at a nearby café before taking a bus back to Würzburg.

SNAKES AND SCORPIONS ABOUND!

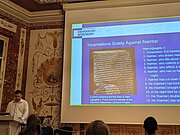

New Investigations in the Early Mesopotamian Incantation Tradition

In the morning of July 23, 2025, Dr. Nicholas M. Gill, a research fellow in Assyriology at Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, led a reading seminar on snake and scorpion incantations for the MagEIA research group and gave a lecture the same evening entitled “Princes, Snakes, and Scorpions: New Investigations in the Early Mesopotamian Incantation Tradition.” His reading seminar and presentation served to outline his ongoing research on archaic incantations, especially those excavated from the ancient city of Ebla, modern Tell Mardikh, located in northwestern Syria.

Orally recited recitations called incantations began to be written down as soon as literary compositions were committed to clay around the middle of the third millennium BCE. These early magical spells had many functions in ancient Mesopotamia; some treat the bites and stings of snakes and scorpions, while others protect the king from witchcraft or prepare the ritual instruments for his investiture.

In contrast to the Mesopotamian incantations found in later historical periods, the incantations dating from the middle of the third millennium BCE through to the end of the first half of the second millennium BCE are not standardized and usually did not become canonized in later times; thus, they often survive on only a small number of tablets.

After providing an overview of the difficulties involved in the interpretation of these archaic Mesopotamian incantations—especially their characteristic phonetic orthography that records the approximate sound of a recited incantation rather than its written meaning and both the abbreviation and variation that permeate the inscribed tablets that record these orally recited compositions—Nicholas M. Gill led the reading group through a selection of snake and scorpion incantations. Together, he and the resident researchers analyzed a group of incantations directed against the bites and stings of these venomous creatures from various historical periods, including the Early Dynastic period (ca. 2500–2350 BCE), the Ur III period (ca. 2112–2004 BCE), and the Old Babylonian period (ca. 2003–1595 BCE).

Following the lunch break, Gill then gave a presentation that provided an overview of his research on the earliest incantations of ancient Mesopotamia. In his lecture, Gill re-examined TM 1975.G.1315, a cuneiform tablet excavated from Ebla which contains a single incantation spread across three columns upon its obverse and additionally has a rubric inscribed in its fourth column. Although Manfred Krebernik (1996) produced a drawn copy of the tablet and offered extensive commentary on individual readings in this incantation, he did not provide a translation. He left the first translation of this tablet to his student Nadezda Rudik (2011: 188–191), who tentatively interpreted the spell to be directed against an unspecified illness, perhaps fever.

During the presentation, Gill offered a new interpretation of TM 1975.G.1315. He argued the incantation is directed against scorpion sting, and shares much in common with other early incantations from Ebla and elsewhere directed against this creature and its painful sting. After establishing the readings of this phonetically written text through recourse to parallel passages and engaging with prior interpretations of the composition, Gill presented a working edition of this incantation, complete with a revised translation as a scorpion spell. This lecture served to demonstrate his approach to the earliest spells of ancient Mesopotamia and provide an example of how to work through compositions of such archaic periods. The working edition of TM 1975.G.1315 which Gill presented before the MagEIA research group will form the basis for a future article. Keep an eye out for it in the future!

Select Bibliography and Further Reading

Krebernik, M. (1984): Die Beschwörungen aus Fara und Ebla. Untersuchungen zur ältesten keilschriftlichen Beschwörungsliteratur. TSO 2. Hildesheim.

Krebernik, M. (1996): Neue Beschwörungen aus Ebla, Vicino Oriente 10, 7–28.

Rudik, N. (2011): “Die Entwicklung der keilschriftlichen sumerischen Beschwörungsliteratur von den Anfängen bis zur Ur III-Zeit.” PhD dissertation, Fredrich-Schiller-Universität Jena.

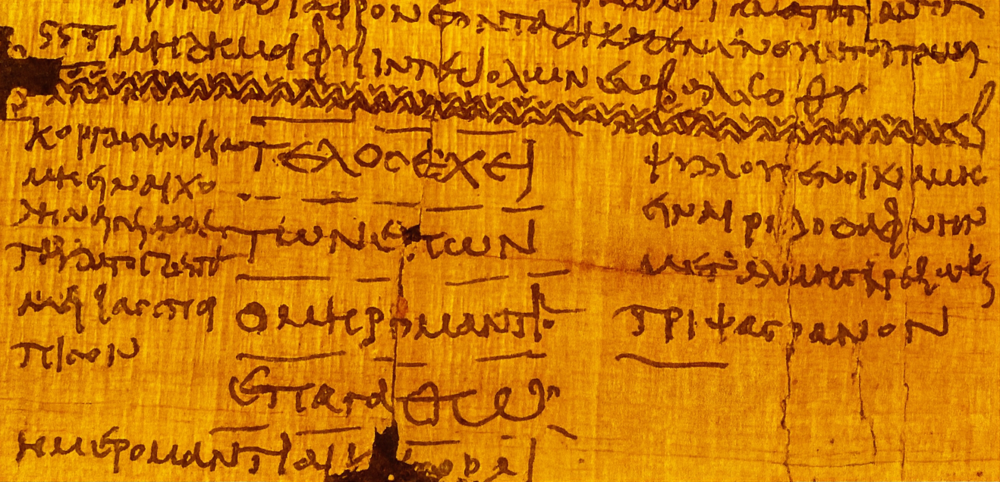

In the Greek and Demotic magical papyri of the second to fourth centuries CE we see a complex process of interaction between the Greek and Egyptian languages, a process which can be seen as a kind of pre-history of the Coptic magical papyri. This interaction arose from the historical relationship between the two languages - Greek as the language of the Roman administration and the cultural elite, and Egyptian as the language of the majority of the population, but whose primary written form, Demotic, was in the process of decline, increasingly restricted to the sphere of the hereditary priesthoods and the copying of religious texts.

This led to a number of forms of close interaction. In the earliest, labelled by Joachim Quack (2017) as ‘Graeco-Egyptian writing’, Egyptian names, phrases, and occasionally entire texts written in Greek script. These early Graeco-Egyptian writings begin in the Ptolemaic period, but are few in number and unsystematic. More developed forms of interaction appear in the early centuries of our era, when we start to see Egyptian temple scribes use Greek to gloss hieratic and demotic texts, clarifying the words and pronunciations of these richer scripts at a time at which fewer scribes had active knowledge of them. In some cases, these Greek glosses are supplemented with Demotic signs to represent sounds present in Egyptian but absent in Greek, creating a system called Old Coptic. In a few cases, we see not only individual words, but entire texts glossed, and it was only a small step for scribes to extract the glosses to produce entire texts written in Old Coptic, a process which was completed by around 100 CE, when original texts, and transcriptions of older texts, appear. While there seem to have been a wide range of Old Coptic systems linked to the geographically dispersed priesthoods, one of these systems was adopted by Christians in the third century, who used it to develop standard Coptic, the final phase of the Egyptian language.

In the magical papyri we can see examples of these complex interactions at work. Interestingly, we occasionally find ‘pseudo-Egyptian’, just as we also find pseudo-Hebrew and pseudo-Aramaic; in PGM XIII.152-153 (IV CE), a text claims to address the god by his true Egyptian name, Aldabiaeim, which a gloss in l. 462 interprets as the Egyptian word for the solar barque; in fact it seems to be a pseudo-Hebrew magical word. Strangely enough, the numerous mistakes made by the copyist of the text implies that he was an Egyptian speaker, although we know for certain that he did not compose the text, since he copies and annotates two different older versions.

There are many cases of real Egyptian loanwords in the magical papyri, however. Some, like the words for ibis (ἴβις) and palm branch (βάϊς) were standard parts of the contemporary Greek lexicon, while others, such as μαντω (from Mꜥnḏ.t), the real name of the sun-god’s day barque, are restricted to the magical papyri. In general, these borrowings reflect the status of the Egyptian language in relation to Greek, referring to religious or, more broadly, ritual concepts and objects. Interestingly, the forms of many of these words seem to reflect the Bohairic dialect from the Western Delta, suggesting that the borrowing into Greek took place in the north of Egypt.

In a few other cases of interaction, we see not only individual words, but entire Egyptian phrases in Greek texts, a kind of ‘code-switching’. In PGM XXXVI.315 (IV CE), part of a spell to open a locked door, the speaker commands a bolt to open, first in Egyptian (αυων νηι αυων νηι τκελλι), and then in Greek (ἀνοίγηθι, ἀνοίγηθι, κλεῖστρον). Again, it is interesting to observe that the Egyptian shows the characteristics of the Faiyumic dialect, typical of the Faiyum oasis, where the papyrus was purchased, and hence probably found.

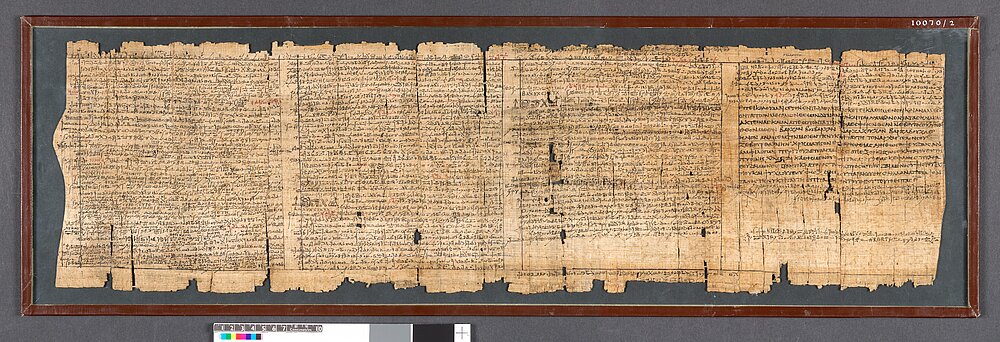

The deepest form of interaction, though, is when entire Egyptian language texts, written in the Old Coptic script, are found in predominantly Greek handbooks. While there are only a few cases of this, the work of scholars such as Jacco Dieleman (2005) and Joachim Quack (2003) has demonstrated that these represent only the surviving examples of a much larger lost literature. The details of the Old Coptic glosses to the Demotic magical papyrus of London and Leiden (GEMF 16/PDM xiv; II CE) show that they are often transliterations into Demotic of Old Coptic texts, which, like the loanwords we have already discussed, seem often to have been composed in the Bohairic dialect. In these cases, Old Coptic magical texts from the humid Delta – from which very few papyri survive – have been preserved by being copied in manuscripts found in the dry deserts of Upper Egypt. Other examples of such Old Coptic texts may be found in PGM III and PGM IV (due to be republished as GEMF 55 & 57), but the best surviving example is the fragmentary BM EA 10808 (GEMF 14; II CE) from Oxyrhynchus in Middle Egypt, which preserves a very complex love or favour spell in Old Coptic script.

But in addition to preserving older magical texts, Old Coptic could also be used for new compositions, and one of the most interesting examples of these is in PGM III.418-420 (III-IV CE), in which Jesus is called “the first power” (ⲡⳓⲱⲥ̣ⲙ· ⲛ̣ⳍⲟⲩⲓⲧ) and “the great god” (ⲡⲛⲉⲧⲟ). While these titles are easily comprehensible within the framework of orthodox Christianity, they use vocabulary drawn from the ancient Egyptian religion – “the great god” (nṯr ꜥꜣ) in particular is a very common title which could be applied to almost any divinity. Texts such as this attest to lost forms of Christianity, in which Egyptians engaged with and tried to translate the ideas of the new religion into their very ancient written language.

This Blog post is based on a short summary of a presentation given as part of the ‘Graeco-Aegyptiaca’ series, co-organised by Palladion in Hungary and UCL in the UK [link: https://www.palladion.hu/en/video-archive/]

Bibliography and Further Reading

- GEMF = Faraone, Christopher and and Sofía Torallas Tovar. 2022. Greek and Egyptian Magical Formularies: Text and Translation, volume 1. California Classical Studies 9. Berkeley: California Classical Studies.

- Dieleman (2005): Jacco Dieleman, Priest, Tongues and Rites. The London-Leiden Magical Manuscripts and Translation in Egyptian Ritual (100–300 CE), Leiden.

- Dosoo (2022): Korshi Dosoo, “The Composition of the Demotic Magical Papyrus of London and Leiden (=PGM/PDM XIV)”, in: Christopher A. Faraone and Sofía Torallas Tovar (eds.), The Greco-Egyptian Magical Formularies: Libraries, Books and Recipes, Ann Arbor, 193–231.

- Johnson (1977): Janet H. Johnson, “The Dialect of the Demotic Magical Papyrus of London and Leiden”, in: Janet H. Johnson and Edward F. Wente (eds.), Studies in Honor of George R. Hughes: January 12, 1977, Chicago, 105–132.

- Love (2016): Edward O. D. Love, Code-Switching with the Gods. The Bilingual (Old Coptic-Greek) Spells of PGM IV (P. Bibliothèque Nationale Supplément Grec. 574) and their Linguistic, Religious, and Socio-Cultural Context in Late Roman Egypt, Berlin.

- Love (2021): Edward O. D. Love, Script Switching in Roman Egypt: Case Studies in Script Conventions, Domains, Shift, and Obsolescence from Hieroglyphic, Hieratic, Demotic, and Old Coptic Manuscripts, Berlin.

- Love (2021): Edward O. D. Love, “The Nature of Old Coptic I: Approaching and Contextualising Old Coptic (§1–4). Old Coptic at Oxyrhynchus (§5)”, in: Journal of Coptic Studies 23, 91–143.

- Love (2022): Edward O. D. Love, “Bilingualism and Mono-/Bigraphia at the Nexus of Magical Traditions: From Egyptian-Greek to Coptic-Arabic Magical Texts”, in: Lajos Berkes (ed.), Christians and Muslims in Early Islamic Egypt: New Texts and Studies, Ann Arbor, 169–201.

- Love (2022): Edward O. D. Love, “The Nature of Old Coptic II: Old Coptic at Tebtunis (§ 6), Soknopaiou Nesos (§ 7), and Narmouthis (§ 8)”, Journal of Coptic Studies 24, 243–281.

- Love (2023): Edward O. D. Love, “The Nature of Old Coptic III: Old Coptic at Akoris (§ 9)”, Journal of Coptic Studies 25, 157–181.

- Quack (2004): Joachim Friedrich Quack, “Griechische und andere Dämonen in den spätdemotischen magischen Texten”, in: Thomas Schneider (ed.), Das Ägyptische und die Sprachen Vorderasiens, Nordafrikas und der Ägäis: Akten des Basler Kolloquiums zum ägytisch-nichtsemitischen Sprachkontakt, Basel 9.–11. Juli 2003, Munster, 427–507.

- Quack (2017): Joachim Friedrich Quack, “How the Coptic Script Came About”, in: Eitan Grossman, Peter Dils, Tonio Sebastian Richter, and Wolfgang Schenkel (eds.), Greek Influence on Egyptian-Coptic: Contact-Induced Change in an Ancient African Language, Hamburg, 27–96.

Divine epithets and the language of the Greek Magical Papyri

As part of his research stay at the University of Würzburg within the DFG-funded research group MagEIA – Magic between Entanglement, Interaction, and Analogy, José Marcos Macedo (University of São Paulo) delivered a lecture on May 8, 2025, offering insight into his current work on the divine epithets found in the Greek magical papyri.

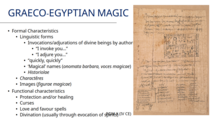

The so-called Greek Magical Papyri (PGM) constitute a corpus of ritual texts primarily dating from the 1st century BCE to the 6th century CE. These texts, preserved in the dry sands of Egypt, are mostly written in Koine Greek, often interspersed with Demotic Egyptian and Old Coptic passages. They contain instructions for private rituals, including spells for protection, healing, cursing, or divination, and reflect the entangled religious landscape of Greco-Egyptian, Jewish, and other traditions.

Macedo’s lecture focused on the role of divine epithets—specific names or descriptive titles used to invoke deities and supernatural forces—in magical practices. These epithets served as powerful linguistic tools, believed to ensure the efficacy of rituals by accurately identifying and addressing divine agents. Practitioners not only drew from established religious vocabulary but also coined new and innovative epithets tailored to ritual needs.

Simple adjectives such as hágios (“holy, sacred”) and hagnós (“pure, holy”) co-exist with elaborate compound constructions and participial phrases like pneúmatos hēníokhe (“holder of the spirit’s reins”) or aithérion drómon heilíssōn hupò tártara gaiēs (“turning airy course beneath earth’s depths”). The repertoire ranges from traditional designations rooted in Homeric and classical usage to unique hapax legomena—epithets attested only once in Greek literature, such as pyriskhēsíphōs (“maintaining light by fire”).

A striking aspect of these texts is the use of voces magicae—artificial names and magical formulas like ABLANATHANALBA or MASKELLI-MASKELLŌ—believed to be the true, secret names of deities and demons. These elements reflect both a sophisticated rhetorical technique and a deeply rooted belief in the performative power of sacred language.

Macedo also emphasized the importance of epithets in the structure of magical hymns, where they contribute to the poetic and persuasive power of invocation. Techniques such as alliteration, parallelism (parallelismus membrorum), associative opposition, and chiastic structures served not only aesthetic purposes but also ritual effectiveness.

The lecture concluded with an overview of Macedo’s current project: an annotated lexicon of divine epithets in the Greek magical papyri. This lexicon aims to cross-reference the epithets found in the papyri with epigraphic, lexicographic, and literary sources up to the 4th/5th century CE. It will include participial and relative clause constructions, formulaic expressions, semantic indices, and syntagmatic chains of epithets—an invaluable tool for further exploring the linguistic creativity and theological imagination embedded in ancient magical practices.

Macedo’s presentation shed light on the dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation in magical language and offered a compelling glimpse into the complex worldview of ancient ritual specialists.

The Power of the Name: Wordplay and Exclusion in Ancient Greek Epic and Magical Texts

by Daniel Kölligan

At the workshop Wordplay and Exclusion, organized by Prof. Esme Winter-Froemel (Chair of Romance Linguistics, University of Würzburg) and held 30–31 May 2025, Daniel Kölligan presented an exploration of how linguistic play operates at the intersection of identity, secrecy, and manipulation – both in ancient Greek epic and in magical texts preserved in the so-called Papyri Graecae Magicae (PGM).

Kölligan’s point of departure is the global phenomenon of name taboos: the widespread belief in the inherent power of names and the social (and magical) consequences of their use, distortion, or concealment. Drawing on anthropological parallels, he emphasizes that in many cultures – including the Homeric world – the use of a personal name can function as a performative act with tangible effects, both benevolent and hostile. Names are not just labels but rigid designators – their utterance is powerful, nearly performative, like a spell, and to name someone may equal to invoke or even control them.

This belief forms the backdrop to one of the most famous scenes in Greek literature: Odysseus’ encounter with Polyphemus in Odyssey 9. Here, Odysseus’ cunning pseudonym Οὖτις Oũtis (‘Nobody’) not only saves him from immediate danger, cleverly sidestepping the danger of name disclosure, but also exemplifies a calculated act of exclusion through wordplay. Later, his fateful revelation of his true name enables the Cyclops’ curse which is deadly to most of Odysseus’ companions. Kölligan shows how the linguistic manipulation of identity (via puns on μῆτις mē̃tis ‘wisdom’ and πολύμητις polúmētis ‘cunning’ vs. μή τις mḗ tis ‘no-one’) weaves a complex narrative of concealment, recognition, and ultimately, downfall.

The paper then shifts from epic to the realm of magical praxis. In the PGM, knowing and using a deity’s “true name” (including foreign or fabricated voces magicae) is key to controlling divine or demonic powers. Here, wordplay often takes the form of multilingual glossolalia, pseudo-etymology, or palindromic sequences (like ABLANATHANALBA) that are as much magical tools as linguistic curiosities. Examples from the PGM reveal a stunning diversity of invented and borrowed words (e.g. from Hebrew, Egyptian, and imagined “birdglyphic” or “falconic” languages). Through these names – crafted through homophony, multilingual punning, or deliberate opacity – practitioners sought to access and command divine forces: in a sense, naming equals binding. The paper highlights examples where the speaker’s knowledge of a deity’s secret names, forms, and attributes serves as leverage to demand obedience.

Importantly, Kölligan stresses the dual function of wordplay: it can include – by creating a shared field of meaning among the informed – and exclude – by withholding full understanding from outsiders or even the subject of manipulation. Whether in the riddling prophecies of Delphi, the ambiguous oracles that mislead kings, or in healing charms based on folk etymologies (like curing the uvula [Greek staphylḗ, Lat. uva] with a grape [staphylḗ, uva] – and amulets shaped like grapes even mimicked the visual shrinking of inflammation), language emerges as both a weapon and a veil.

In sum, the presentation showed that the Greek epic and magical traditions both rest on the conviction that names are not just symbols (and wordplay is never just play) – they are the person, the power, the peril. Far from Saussurean theory, these traditions share a belief in the non-arbitrariness of language and treat formal resemblance as ontologically meaningful: a name is not just a label, but an essence.

Official programme and more: Wordplay and Exclusion (30/05–31/05/2025)

Facing the Underworld: Jonathan Beltz on Sumerian Death-Demons and How to Deal with Them

In the most recent episode of the MagEIA Podcast, Jonathan Beltz delves into the haunting world of Sumerian death-demons and the protective strategies developed to confront them:

https://shwep.net/2025/03/26/jonathan-beltz-on-sumerian-death-demons-and-how-to-deal-with-them/

The episode begins with a historical overview of ancient Sumerian civilization, introducing listeners to the cultural and religious landscape of early Mesopotamia. Beltz then turns to the ever-present threat of underworld entities, particularly those associated with sudden illness, unexplained death, and spiritual affliction, like the Udug, a disease-bearing entity; the Gala, a kind of rogue entity, also prone to bringing disease and of course the infamous Namtar the Sumerian ‘angel of death/grim reaper’.

A range of textual sources is explored, including incantation tablets and ritual texts from the famous “Maqlû” and “Šurpu” series. These texts outline protective rites, purificatory actions, and summoning formulas aimed at diagnosing, repelling, or neutralizing demonic threats.

Equally important is the material evidence: Beltz discusses artifacts such as clay figurines, amulets, and ritual paraphernalia used by exorcists (āšipu) and healers. He emphasizes how such objects functioned within elaborate magic-religious ceremonies, revealing the fine line between healing, protection, and the manipulation of divine or infernal forces.

The episode also touches on the role of liminality in Sumerian demonology—thresholds, twilight hours, and transitional states all marked zones of increased spiritual vulnerability. Beltz draws attention to the ways in which both personal and communal ritual activity was mobilized to fortify boundaries between the living and the dead.

Magic and Everyday Life in Late Antique Egypt – Korshi Dosoo on Papyri Copticae Magicae (de Gruyter, 2023)

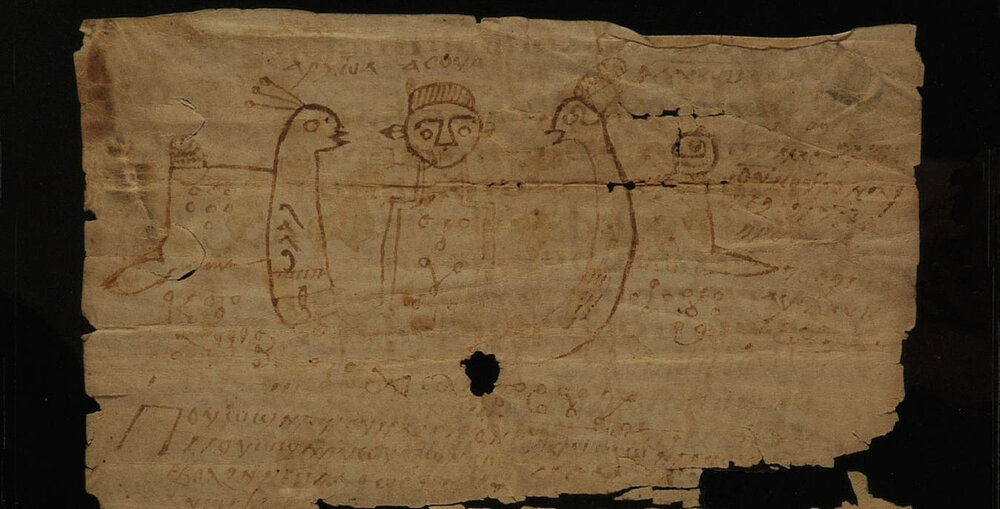

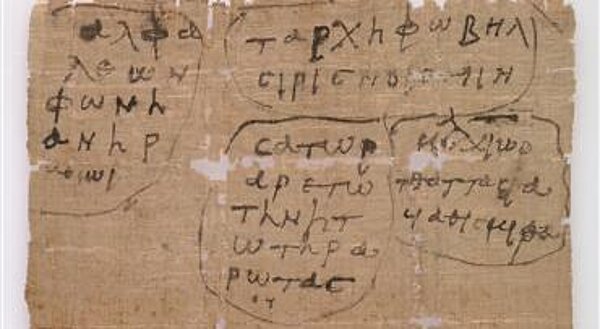

Magical love spell decorated with two doves, 1st century BC; [Dutch National Museum of Antiquities]

In this episode of the New Books in Ancient History podcast, Egyptologists Korshi Dosoo presents his - together with Markéta Preininger- new volume Papyri Copticae Magicae: Coptic Magical Texts, Volume 1: Formularies. The book offers a carefully edited and annotated collection of 37 Coptic magical manuscripts, making these often-overlooked sources accessible to a broader audience beyond the niche community of Coptic specialists.

The manuscripts span a wide range of magical practices from late antique Egypt, including love spells, healing rituals, curses, and exorcisms. Among the texts, listeners will discover formulas for easing stomach pain, inducing restful sleep, enhancing singing voice, or attracting the attention of a one-sided love interest. The manuscripts also include curious recipes calling for ingredients such as bee sweat, horse saliva, frog blood, incense, and various plant substances.

These texts provide vivid insight into the everyday concerns of people in late antiquity—love, health, justice, and spiritual protection—while reflecting the linguistic, religious, and cultural complexity of Coptic Egypt

You can listen to it at newbooksnetwork.com

Or on Spotify

(Images of) Women in the Demotic and Greek erotic spells

On the evening of May 5, 2025, Dr. Svenja Nagel, post-doc researcher of the MagEIA core team, held a lecture with the title "Frauen(bilder) in den demotischen und griechischen erotischen Zaubersprüchen" as part of the WAZ lecture series "Frauenbilder der Antike" (see: https://www.uni-wuerzburg.de/forschung/waz/aktuelles/ringvorlesungen/). The event was kindly hosted by the Burkardushaus Würzburg.

A vast corpus of Demotic and Greek magical handbooks from Graeco-Roman Egypt has been preserved, containing both collections of ritual recipes and examples of activated texts and objects used in magical practice. A significant portion of these sources deals with sexuality and love. This so-called erotic magic encompasses ritual techniques aimed at influencing one’s own sexual life or that of others — to gain control over desire, attraction, and related physical and social dynamics.

In her lecture, Svenja Nagel presented a detailed analysis of key phraseology and ritual procedures in spells of attraction (agogai), love bindings (philtrokatadesmoi), and aphrodisiacs. Central to the discussion was the way these spells conceptualize the body of the intended target, and how this conceptualization contributes to the ritual mechanics of the magical act.

The instructions found in the handbooks are typically designed for a male practitioner acting upon a female target, reflecting a distinctly male perspective on the female body and female sexuality. However, Nagel highlighted that applied and individualized magical spells tell a more complex story: women also performed these rituals against men, and in some cases, both men and women used them in the context of same-sex desire. While less frequently attested, these examples reveal a broader range of practitioners and intentions than the normative male-to-female model suggests.

Finally, the lecture contextualized these representations of women by drawing on literary and documentary evidence from Graeco-Roman Egypt, as well as earlier Egyptian traditions. Through this lens, the images and roles of women found in erotic magical texts emerge not only as reflections of ritual practice, but also as indicators of shifting cultural norms around gender, sexuality, and power.

The invitation to come to Würzburg and spend six months as a fellow at the DFG MαgEIA project came at a particularly opportune moment for me. Having worked on late antique Jewish Aramaic magic for quite some years and shifted the majority of my attention to Ethiopian materials in the last decade it was time to take stock and consolidate some of my thoughts and ideas. Being a relative newcomer to Ethiopian Studies, despite a lifelong personal connection with Ethiopia itself, and having managed to publish a few smaller pieces of research in the form of book chapters and journal articles it was time to attempt a small book, an edition of a special text. This fellowship offered not only the time and ideal physical conditions, it also offered the unique chance to join forces with Professor Mersha A. Mengistie to collaborate with on the realisation of this book; to combine my understanding of the history and culture of magic in the Semitic speaking world with Mersha’s unparalleled knowledge and grasp of the history and culture of the Ethiopian Orthodox Twahedo Church (EOTC).

The centre-piece of this book is a text known as the Lefafä ṣǝdq (LS), The Scroll of righteousness, that was first published in 1908 by B. A. Turayev, and then in 1929 by E. A. W. Budge, and later in 1940 in another version, by S. Euringer. It is probably fair to say that it was Budge’s edition, with his imaginative claims, talent at reaching a wider audience and his wonderful (if not somewhat confusing) title “Bandlet of Righteousness: An Ethiopian Book of the Dead” that made this text so well known. It has, furthermore, come to be known as a (‘the’ ?) prime example of Ethiopian magical literature. Almost a century later the text Budge thought to be a rare occurrence is now known in many witnesses; I have seen well over thirty and know of more. Our aim is not only to produce a new edition of this text but provide an account of what we can learn about it, and from it about Ethiopian magical literature more generally, and as importantly of those who produced (and still produce) it.

With only a couple of weeks to go I think that we are a hair’s breadth of distance from concluding a first full draft that we will be submitting to Würzburg University Press for publication. That, however, is not the only publication in preparation. There is a long scroll text from the Rylands collection that I transcribed in 2017 which Mersha and I are also editing for publication. The time spent together with Mersha has resulted in many long discussions on a wide variety of texts and aspects of Ethiopian, Jewish and Christian magically related issues. We shared thoughts on philology, theology, folklore, mythology and more. We discussed the nature of the work of scribes who produced magical texts, probing their part in curating such textual objects as they assisted their clients deal with their woes, as they navigate(d) the world they believe(d) is inhabited by supernatural entities that affect(ed) their well-being.

MαgEIA offered so much more than the very personal of requirements (office, computer, help with finding accommodation, etc...), it offered the unique chance to work within a group of like-minded researchers all of whom deal with magical texts and cultures from different periods. Our bi-weekly seminars offered an opportunity to share and learn, as did the many coffees, lunches and chats in the corridor of MαgEIA haus, and the streets and alleys of the charming city of Würzburg.

There was nothing that I wanted or needed that was not provided by the three PIs and MαgEIA’s administrator Anne Noster. Most important was their friendship that came with collegiate exchange, feedback and support that will undoubtedly affect my work and life evermore.

Discovery is always a process, one that requires time to think and the opportunity to share. As my time with MαgEIA rolled on, mine was what I can honestly best refer to as a “magical mystery tour”; one of constant discovery as research and writing should be, and for me inevitably is, a creative process. Ethiopian magical texts and the academic study of magic more generally, have received relatively little attention. There are some fantastic editions of texts but a wider approach such as has been accorded to Jewish, Greek, Assyriological, Ancient Egyptian, or Coptic materials has not been forthcoming. Discoveries regarding the LS that will have implications for the study of other Ethiopian magical texts include things like the identification of some of the materials that scribes have drawn on for the production of their formulae, a nuanced appreciation of the curatorial input of individual scribes into the versions they produced, and the introduction of glosses later on in the life of the text as it was transmitted over a period of at least four hundred years.

Having retired from the university of Southampton some four years ago I have continued to be very research active. Uni Würzburg has provided me with an affiliation that has become a new home to me, a community of colleagues and friends, many of whom I have now developed critical friendships with through which my work is enriched. MαgEIA has also provided me with an affiliate home for another of my projects – check it out here: Ethiopian Painters.

I will be back in MαgEIA Haus in November to give a first account of another project of mine that starts on the first of April which is titled “Incantations and recipes to ward off snakes and protect from snakebites in Ethiopian manuscripts” (https://www.leverhulme.ac.uk/emeritus-fellowships/levene).

MagEIA Evening at SCIAS: Magic, Language, and Intelligence

On March 24, 2025, the Siebold-Collegium Institute for Advanced Studies (SCIAS) hosted an engaging evening featuring international researchers from the MagEIA group and Kurdish linguistics experts. Held at the Welz-Haus in Würzburg, the event explored themes of magical-medical traditions in Ethiopia, Mesopotamian rituals, and linguistic developments in Kurdish. Scholars and guests gathered to discuss how ancient knowledge systems continue to shape contemporary thought.

Professor Mersha Mengistie (Addis Ababa University) opened with "Yaqalam ʾAbǝnnat: The Magico-Medical Path to Intelligence in Ethiopia." His talk examined a unique Ethiopian educational system that enhances cognitive abilities through psychotropic substances and ritual recitations. Rooted in deep cultural traditions, this practice is believed to sharpen intellect and heighten spiritual awareness. Mengistie provided historical context and discussed its modern implications.

Dr. Frank Simons (Trinity College Dublin) followed with "Burn Your Way to Health and Happiness," offering an in-depth look at the Mesopotamian Šurpu ritual. This purification ceremony, dating back to ancient Babylonian times, was performed when individuals were uncertain which deity they had offended. Through fire, the ritual aimed to cleanse misfortune and restore harmony. Simons presented recent findings from cuneiform texts that reveal how these rites were integrated into broader Mesopotamian healing practices.

The final presentation, "Archaism and Innovation in Kurdish," was delivered by Dr. Shuan Karim (University of Cambridge). He explored the historical evolution of Kurdish languages, demonstrating that languages are not simply "old" but are constantly adapting. Through linguistic analysis, Karim illustrated how Kurdish balances preservation of archaic elements with ongoing innovation. His talk also touched on spatial linguistics, showing how geography influences language variation and change.

The evening concluded with a lively networking reception, where attendees engaged in discussions about the intersection of language, magic, and medicine. The diverse presentations highlighted the rich interplay between ancient traditions and modern scholarship, leaving participants with a deeper appreciation of the ways in which historical knowledge informs contemporary studies.

The Visual Sound of Symbols: Aural and Visual Imagery in Graeco-Egyptian voces magicae

On January 15 Panagiota Sarischouli held a lecture on "The Visual Sound of Symbols: Aural and Visual Imagery in Graeco-Egyptian voces magicae" at the MagEIA Haus. In the following she summarises her talk in a few words:

One of the most notable techniques in Graeco-Egyptian magic is the use of voces magicae—seemingly incomprehensible strings of letters or words believed to carry inherent sacredness. Originally designed for oral communication with the divine during private rituals, these magical terms were also thought to hold divine power in their material form. However, the exact nature of this belief remains elusive to modern scholars. While voces magicae are most commonly associated with Roman and Late Antique periods, the use of foreign or strange-sounding words in magical contexts dates back much earlier, to traditions such as Assyrian and Egyptian magic from the 2nd millennium BCE.

The primary function of voces magicae was to produce a powerful auditory effect, often achieved through rhythmic patterns, repetition, and onomatopoeia. Yet, many of these words also aimed to invoke a visual or material power, with the words themselves believed to make the magic tangible and visible. This duality of orality and visuality was not seen as separate but as interdependent and complementary components of ritual practice. Thus, voces magicae often appeared within complex textual structures that required both vocal and visual engagement, and can generally be categorized into three types: palindromes, isopsephistic sequences, and geometric word formations. My focus is on the latter, as these intricate arrangements of words or vowels were purposefully crafted to either enhance or diminish the magical potency of the text, reflecting a belief in the combined power of sound and sight in Graeco-Egyptian ritual practice. These geometric formations have been compared to Hellenistic technopaignia, a genre of poems that generate visual imagery through variations in meter and verse structure. However, applying this comparison to Graeco-Egyptian magical incantations may not be entirely appropriate. While both involve structured composition, magical texts differ fundamentally from works of art or literature, which often prioritize personal expression, aesthetics, and storytelling. Magical incantations, in contrast, were primarily concerned with the preservation, transmission, and transformation of esoteric knowledge, often with a practical and functional purpose rather than a symbolic or artistic one.

In this context, I have sought to historicize the phenomenon of voces magicae, particularly by examining the evolutionary trajectory of magical schematic formations. This progression—from simpler to more complex structures over time—illuminates how this magical technique evolved. Ultimately, this analysis underscores the profound interconnection between text, visuality, and ritual in Graeco-Egyptian magic, revealing how form and function converged to create powerful and transformative magical practices.

I am very grateful to the MagEIA principal investigators, Prof. Dr. Daniel Schwemer, Prof. Dr. Daniel Kölligan, and Prof. Dr. Martin Stadler, for giving me the opportunity to present my work to the MagEIA team, and for the valuable feedback provided by this exceptional group of experts on my ongoing research.

Coptic Magical Texts and Their Contexts: Exploring Language, Ritual, and Religious Transformation in Late Antiquity

Coptic is the latest form of the Egyptian language, written in a modified version of the Greek alphabet from around the third century of the common era onwards. While it was often a subordinate language – with Greek and later Arabic as the languages of government, culture and science – it would have been the mother-tongue of most Egyptians until around the tenth century or so, when Arabic began to become predominant even among Egyptian Christians. For this reason, magical texts in Coptic allow us to see very clearly the responses of normal men and women to the crises in their lives which led to them seeking magical help – problems of health, requiring healing amulets, or social problems requiring love spells or attacks in the form of curses. We also see in them the process of religious change, with the earliest (Old) Coptic texts containing invocations of the traditional Egyptian deities, while later ones are predominantly Christian, but often incorporate figures drawn from Gnosticism, and, from around the tenth century, the influence of Islam.

Better understanding the Coptic magical papyri has been the goal of my two projects The Coptic Magical Papyri: Vernacular Religion in Late Roman and Early Islamic Egypt (2018-2023) and Corpus of Coptic Magical Formularies (2024-2027), and I was very grateful to have the chance to explore this topic more within the scope of MagEIA for six months in 2024.

My work over this time focused on several smaller ongoing projects. Much of my ongoing work consists of editing Greek and Coptic texts, either magical, or testifying to related popular religious practices, and MagEIA was very helpful in providing a forum to discuss this translation work. Three new translations which I worked on during this time will be published in the near future. The first is of a pair of sixth-century oracle questions in Greek addressed to Saint Philoxenos, who had a shrine at Oxyrhynchus, asking whether the questioner should buy a banking business. This practice of addressing questions was a very ancient one in Egypt, attested by the Third Intermediate Period, and revived in the Christian period in the context of saints’ shrines. The second is a rare Coptic ritual for bowl divination, dating to the eighth or ninth century, in which a spirit would be summoned to appear in a bowl of water and answer questions. The third is a small amulet against snakebites which is “powered” by a number of interesting names – the famous Sator-sequence of Latin origin, the names of the three magi (often known as “wise men”) from the Gospel of Matthew, and so on. The first two of these will be published in the forthcoming collection Prayer in the Ancient Mediterranean World, and the third in a volume entitled Textual Amulets in the Mediterranean World edited by Christopher A. Faraone, Carolina López-Ruiz and Sofía Torallas Tovar.

Another important question in my work is the presence of Coptic in the early, primarily Greek-language handbooks. These usually represent a range of archaic forms of the language, known as Old Coptic. Despite the fact that Old Coptic is poorly attested, and imperfectly understood, it is very important for our understanding of the Egyptian language as a whole. Old Coptic texts often preserve grammatical forms and vocabulary found in hieroglyphic and demotic texts but lost in standard Christian Coptic. They also reveal the process by which Coptic itself developed: in the early centuries of our era, Egyptian priests developed Old Coptic systems as a tool to help them in reading the older script. One of these Old Coptic systems was apparently adopted by Christians around the third century, perhaps specifically to translate the Bible and other Christian texts. The details of this process remain unclear, but the study of Old Coptic texts, many of which are magical, can help us understand this process better. During my time as a fellow, I produced a two-part study of the Egyptian language in PGM IV, the “Great Magical Papyrus of Paris”, the largest surviving Greek magical text, dated to the fourth century CE. This study looked at Egyptian words borrowed into Greek – both practical words, like kyphi (a type of incense), used in ritual instructions, and the names of gods like Psoi (Pshai, a serpentine god of fate in Roman Egypt), often used in magical formulae. It also examined the six Old Coptic sections in this predominantly Greek work, exploring their linguistic features and their relationship to older Egyptian and later standard Coptic. This work revealed that the Egyptian-language words and sections contain many different influences – some of the texts seem to be hundreds of years older than the manuscript which preserves them, and to have been composed in Lower Egypt, where Alexandria – the presumed place of composition of many magical texts – was located, but from which we have almost no papyri. Other texts seem to have been more local, showing signs of circulation in the Theban region around modern Luxor where the manuscript was found. Both of these articles will be published in a larger study of PGM IV in preparation by its editors, Christopher A. Faraone and Sofía Torallas Tovar.

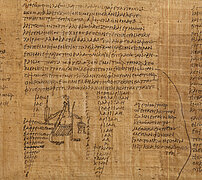

A third ongoing theme of my work is the study of drawings in the magical papyri, and so the last article I worked on in this time is a reflexion on the use of images in Graeco-Egyptian magic – both papyri and gems – and the way in which it continues and transforms older Egyptian ideas about the power of apparently inanimate images. This study will be published in a volume entitled Immortal Egypt, edited by Luisa Capodieci and Laurent Bricault, resulting from a series of colloquia of the same title.

I am very grateful to the MagEIA principal investigators, Prof. Dr. Daniel Schwemer, Prof. Dr. Daniel Kölligan, Prof. Dr. Martin Stadler, for offering me the chance to work with them and the other members of the MagEIA team, including my fellow fellows. The discussions in the weekly seminars, as well as the informal talks over lunch, dinner and coffee, and the regular public lectures were a wonderful way for me to learn more about other magical and ritual traditions, and get helpful feedback on my ongoing work. I look forward to working more with them as their neighbour in the new Corpus of Coptic Magical Formularies project, which began in September of last year.

MagEIA Evening at SCIAS

On Thursday evening, the three MagEIA Fellows Gaby Abou Samra, Jon Beltz, and Dan Levene were invited to present at the SCIAS Guest Lectures.

At the beginning of the MagEIA evening, Professor Gaby Abou Samra (Lebanese University, Lebanon) spoke on the topic of ‘Magical literature: bowls and amulets’. His lecture targeted the iconographic and textual analysis of magic bowls in Aramaic, Syriac and Mandaic which he then compared with other Semitic texts.

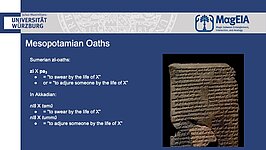

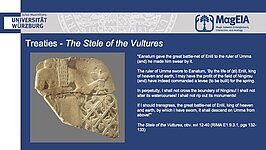

Afterwards, Junior Fellow Dr Jon Beltz, who holds a doctorate in Assyriology from Yale University, had a talk on ‘Swearing at Demons: Research on Mesopotamian Oath Magic’. Jon examined how Sumerians adapted the use of oaths from legal contexts and treaties in the mid- to late third millennium BCE to exorcism practices, binding demons to protect patients. He discussed his recent publications on amulet texts and incantations that employed this technique, including his work reconstructing the late Sumerian text Lugal-Namtar. Jon plans to further explore how legal metaphors in these texts influenced ancient Mesopotamian conceptions of demons and the interplay between legal and magical language.

The evening was rounded off with the lecture ‘Illness and Healing - An Ethiopian view’ by Professor Dan Levene from the University of Southampton, UK. This presentation was a short but very direct insight into popular belief in Ethiopia regarding wellbeing and the absence of it. A place where people understand their condition to be linked to the divine and supernatural entities such as demons, spirits and angels. This is not as far removed as beliefs of people in the west whom in churches, mosques, Hindu and Sikh temples appeal, each according to their beliefs, to help with illness and other difficulties in life.

31st October – 2nd November 2024: the 1st MagEIA Symposium

Between Thursday, 31 October and Saturday, 2 November 2024 the MagEIA Centre for Advanced Studies held its first international Symposium. Several guests from all over the world joined at the Burkardushaus conference center in Würzburg to share their research on the topic “Actors, Aggressors and Agency in Ancient Magical Texts”.

After a welcome address by Daniel Schwemer, Christopher Faraone (Chicago) opened the Symposium with the first talk, titled “‘And you, o holy chthonic gods, from below send a ghost into the light!’ Aeschylus’ Persians 623-71 and the Longue Durée of Ancient Necromancy”. Most scholars believe that the necromantic scene in Aeschylus’ Persians depicted a genuine Greek ritual, but recent skepticism suggests it may instead reflect a literary tradition rather than real practices. However, the scene’s structure mirrors rituals in ancient Mesopotamian texts and later Greek magical recipes, indicating a long-standing tradition of necromancy that likely influenced Aeschylus.

Afterwards Beatrice Baragli (Würzburg, MagEIA) joined the Symposium via Zoom and gave her talk “Of Scapegoats, Birds, and the Rest: The King and All His Substitutes in the Mesopotamian Bīt rimki Ritual”. The Bīt rimki ritual, a complex royal purification ritual from ancient Assyria and Babylonia, was performed to protect the king from various evils through extensive prayers and ritual actions involving various different animals and captives that were used as ‘scapegoats’. The speaker elaborated how these ritual elements relate to kingship and the specific protective relationship between the banished entities and the king.

After the coffee break Daniel Kölligan (Würzburg, MagEIA) presented his talk “Structuring Actors in Magical Texts”. Human psychological and physical phenomena, like fear, sleep, or old age, have often been attributed to supernatural forces, which are represented as external agents in various cultural texts and traditions. With a particular focus on possible cultural and linguistic contacts, he examined how these supernatural actors—whether minimally or fully personified—are adapted within magical traditions and rituals, influencing both the structure of the texts and the characteristics of the entities themselves.

Subsequently Bernd-Christian Otto (Erlangen) moved on with “CAS-E and MagEIA: Exploring Synchronicities between two Bavarian Centers for Advanced Studies”. These two Centers for Advanced Studies focusing on magic and esoteric practices, funded by the German Research Foundation and based in Bavaria, have begun collaborative research, with the Erlangen center (CAS-E) examining contemporary global perspectives since April 2022. The speaker outlined CAS-E’s structure and research programme, and discussed potential synergies with MagEIA as well as important points for discussion, e.g. how to cope with emic terminologies vs. etic definitions.

To round off the first symposium day, Gideon Bohak (Tel Aviv) held the Keynote Lecture on “Conceptualizing Magicians and Witches in the Ancient World”. He argued that understanding ancient concepts of magicians and witches is made complicated by Western cultural biases, by the diversity of terms across ancient languages, and the assumption of a unified definition. His talk suggested that overcoming these issues requires close, multilingual textual analysis, and collaborative scholarship, which is indeed a key focus of the MagEIA project.

The Symposium continued in the morning of Friday 1 November. Sara Chiarini (Hamburg) held the first talk about “The Social Agency of Ancient Curse Tablets”. Her paper examined the agency of ancient curse tablets—inscribed lead objects intended to harm specific targets—which were often treated as embodiments of the curse's intended effects, similar to figurines used in rituals. Drawing on Alfred Gell’s theory of social agency, she argued that practitioners viewed these tablets as powerful substitutes for human flesh, enacting symbolic violence to manifest the curse.

Afterwards Theresa Roth (Berlin) and Matthias Donners (Marburg) presented a joint paper on “Conceptualizations and Linguistic Representations of Antagonicity in (Gallo-)Roman Curse Tablets”. Their talk had a look on how Latin and Gaulish curse tablets linguistically represent the antagonistic relationship between the author and the target, exploring variations in conceptualization, lexical choices, and agency across different texts, languages, and cultures.

Jessica Lamont (New Haven) continued with a talk on “Early Greek Magic in Sicily: Divinities, the Dead, and Human Participants”. She explored the oldest Greek curse tablets from western Sicily, analyzing the deities invoked, the human agents involved, and the social, legal, and geopolitical factors that contributed to the emergence of this ritual practice around 500 BCE. She demonstrated that they were first deployed in legal contexts by the aristocratic class.

After the first coffee break Rüdiger Schmitt (Münster) spoke about “Witches as Actors in the Hebrew Bible: Mysogynic Polemics and/or Female Healers?”. He explored the gendered dynamics of witchcraft accusations in the Hebrew Bible, particularly how female witches are stereotyped (e.g. through an association between witchcraft and harlotry) and linked to foreign religions. Furthermore, possible social realities behind such accusations and the monopolization of ritual authority by biblical authors were discussed.

Charlotte Rose (Würzburg, MagEIA) took up the focus on women, and introduced the audience into the realm of Egyptian magic with her talk on “Egyptian Women and their Gods vs. the Evil Dead and their Demons”. Her paper examined the roles of medical-magical practitioners, patients, spirits, demons, and magical materials in gynecological spells from ancient Egypt, with a focus on the gendered agency and the interplay of deities, demons and patients in treatments.

Frank Simon’s (Würzburg, MagEIA) talk “Get Them to Do the Easy Bits – The Division of Labour in Šurpu and Other Rituals” explored the roles and spoken lines of participants in Mesopotamian rituals, focusing on the Šurpu (“Burning”) series and a newly discovered copy of the Šurpu Ritual Tablet. He demonstrated that the patient was only meant to recite those parts of the incantations that directly involved himself and were relatively easy or repetitive, whereas most parts were spoken by the exorcist.

After the lunch break, Gaby Abou Samra (Würzburg, MagEIA) opened the afternoon session with his talk on “A New Syriac Manichaean Magical Bowl”. He presented an unpublished Syriac magical text in Manichaean script on a ceramic bowl from late antiquity Mesopotamia, which was written for a woman and her family. In particular, he explored its incantations for protection against evil spirits, which include repetitions of the name of god as a powerful agent, and provided insights into the magical rituals and religious beliefs of the period.

Mersha Alehegne Mengistie (Würzburg, MagEIA) followed with “Unlocking the Power of Words: The Codex as a Sacred Vessel in Ethiopian Magical Rituals”. His presentation explored the significant role of Ethiopian codices in magical rituals, highlighting their power beyond mere texts as essential tools for healing, protection, and spiritual connection, drawing insights from magical formulas and observations of practitioners and their treatment of the texts.

Before the coffee break, Dan Levene (Würzburg, MagEIA) gave the talk “Curating the Numinous: Ethiopian ጽሕፈት ṣəḥfat (scribal) magic” on the Lefafe Tsedeq (LS), a text which exhibits significant textual variation, with surviving manuscripts dating back to the 17th century, yet likely containing elements from earlier traditions. His presentation examined the human and supernatural actors involved in the LS’s ritual use, supported by both historical manuscripts and living informants who maintain its performative practices.

In the later afternoon Jon Beltz (Würzburg, MagEIA) continued with “‘Be Adjured by Heaven, Be Adjured by Earth:’ Oath Language in Mesopotamian Incantations”. Oaths in Mesopotamian society were essential tools for ensuring trust and could create new realities, paralleling the function of incantations like the “zi—pa formula” that imposed oaths on demons to exorcise them, thereby extending familiar human practices of enforced oaths into the supernatural realm. He analyzed Sumerian and Akkadian oaths in various texts, showing how oaths were adapted to control demonic forces much as they regulated human interactions and treaties.

The last two lectures of the day dealt with Ancient Egypt. Susanne Töpfer (Turin) talked about “Magical Aspects in Some Temple Rituals for the Protection of Pharaoh from Tebtunis”. The five fragmentary Tebtunis manuscripts from the 2nd century CE detail temple rituals performed by priests to protect the Pharaoh, distinguishing the king’s dual role as both a ritual performer and a divine beneficiary identified with gods. The speaker pointed out parallels to texts on amulets and temple walls, and discussed the connection to the Roman Emperor's affirmation as Egyptian Pharaoh.

Svenja Nagel (Würzburg, MagEIA) concluded the day with her talk “Pharaoh, Help Thyself! Empowering the King against Enemies and Dangers in the Pyramid Texts”. The Egyptian Pyramid Texts, inscribed in Old Kingdom pyramids, consist of spells intended to ensure the deceased Pharaoh’s resurrection and protection in the afterlife, empowering him to overcome various dangers with the aid of deities and his own conjurations. Focusing on the apotropaic spells, she discussed the rhetoric techniques and the roles assumed by the king to protect himself and maintain his powerful status among the gods.

On Saturday 2 November, the conference continued until midday, with four more presentations:

The first speaker was Sofía Torallas Tovar (Chicago/Princeton) who gave a talk on “Dream Requests in the Magical Formularies”. In Greco-Egyptian magic, dream requests were a common practice for seeking divine insight or healing, with evidence from both papyri and literary sources like Artemidoros and Galen. By analysing these two types of sources in comparison, the speaker offered contrasting perspectives on the nature and societal views of these practices which changed over time.

Daniel Schwemer (Würzburg, MagEIA) followed up with his lecture on “Twin, Exorcist, and Ruler of the World. The Remarkable Career of a Valiant Doorkeeper”. Lugalirra, a lesser-known Babylonian deity typically depicted as a gatekeeper of the netherworld alongside his twin Meslamta’ea, unexpectedly takes on a central role in the “Bīt mēseri” ritual, where he serves as a guardian and exorcist protecting against demons. This ritual highlights Lugalirra’s multifaceted roles beyond gatekeeping, showing him as a warrior, master of ceremonies, and even a universal ruler, reflecting the theological creativity within Babylonian magical texts.

Next, Giulia Torri (Florence) talked about “Divine Intervention in Hittite ritual Practice”. In Hittite ritual texts, deities are not merely recipients of offerings but are actively invoked to participate in rituals, sometimes performing mythic actions to aid in resolving ritual challenges. This divine involvement often includes symbolic actions, such as absorbing impurities through figurines, mirroring the deity’s mythic role and enhancing the ritual’s efficacy through the performer’s recitations and symbolic gestures.

The final talk was given by Martin Stadler (Würzburg, MagEIA) on “Actors, Aggressors, and Agency in the Horus Temple of Edfu: The North Wall of the Enclosure Wall”. The temple of Horus at Edfu, an exceptionally well preserved site, contains inscriptions focused on protective and apotropaic rituals, especially those warding off evil forces, with significant texts inscribed on the inner enclosure wall during Ptolemy IX's reign. He analyzed two key protective rituals—“Protection of the House” and “Guarding the Body”—which, embedded with references to spells against the Evil Eye and other dangers, offer insights into ritual agency and the symbolic roles of these inscriptions.

Around lunch time the Symposium was concluded with final remarks and a farewell to all of MagEIA’s guests and listeners.

Seeing the Unseen: The Side Characters in Hittite Rituals

In the ancient Near East, magic manifested through symbolic actions and verbal utterances meant to activate supernatural powers to achieve specific goals. These practices were intricately linked with the religious and social norms of the society. As a significant social phenomenon, magic plays a crucial role in social control, decision-making processes, and religious life, particularly during times of crisis. The repeated recording of magic texts and the use of symbolic language illustrate how relationships between the natural world and organized cultural environments were articulated through language. Thus, the comparative study of these texts provides both valuable linguistic insights and deepens our understanding of the semantic worlds of ancient societies, offering a richer perspective on cross-cultural dynamics.

My research at MagEIA has focused on the identification of the secondary figures referenced in Hittite magical rituals and on an examination of their roles within these practices. Until now, most of the literature on Hittite ritual has focused on the ritual practitioners. However, the texts also refer to subsidiary characters, who, though not the main focus, were essential for the proper functioning of a ritual. The primary objective of my research is to shift the focus from the main characters to those who have been largely overlooked. By shining a light on these individuals, it is possible to gain insights into the diversity of participants in magical practices and to enhance our understanding of the overall organization. With regard to the Hittite ritual texts, the side characters can be grouped into three different categories. The first category comprises cultic and administrative officials, who have auxiliary functions in these practices but never perform a magic ritual alone. They are involved in the performance with the specific responsibility of adhering to designated actions. This group is evident in the rituals performed for the Hittite king and royal family as well as in military rituals. The second category encompasses artisans and professionals such as blacksmiths, shepherds, weavers, barbers, bakers, cooks, and many others. These individuals either directly participated in certain parts of magical practices or, on occasion, their typical characteristics were attested in the magical spells through analogies. Finally, the third category comprises individuals from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds, who may also be considered marginalized groups. These include prisoners, slaves, war captives, servants, the blind and deaf, women, and children. The most accurate examples of these individuals can be found in the substitution and purification rites.

Given the vast number of Hittite ritual texts (ca. 4,000 fragments), my research has been based on two approaches: (1) a systematic examination of ritual texts and the creation of a database, and (2) a critical review of existing literature. The outcomes of this research will be published in two articles: one addressing the first two categories of secondary figures, and the second focusing on the marginalized groups.

During my four-month research stay as a fellow at MagEIA, I was able to focus on my research while expanding my knowledge of ancient Near Eastern magic texts. It was a pleasure to engage in numerous fruitful discussions with colleagues, both in the twice-weekly MagEIA seminars and in informal settings such as lunches and dinners. Additionally, I had the privilege of attending evening lectures in the Toskanasaal of the Würzburg Residence, where I had the opportunity to hear esteemed scholars of ancient Near Eastern studies and other fields discuss their work. I would like to express my sincere thanks to the principal investigators of the project, Prof. Dr. Daniel Schwemer (as my Gastgeber), Prof. Dr. Daniel Kölligan, Prof. Dr. Martin Stadler, and the entire MagEIA team as well as to the Siebold-Collegium (SCIAS) for providing accommodation. The research period at MagEIA was both productive and enjoyable, set in the beautiful city of Würzburg.

Korshi Dosoo: “Causers of Strife and Child Murderers – Demons and Other Malign Beings in the Coptic Magical Papyri”

08.07.2024

On Tuesday, 8 July 2024, Korshi Dosoo (Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg) presented the final lecture of this semester’s MagEIA Ringvorlesung series, “Causers of Strife and Child Murderers: Demons and Other Malign Beings in the Coptic Magical Papyri” (original title „Unruhestifter und Kindsmörder – Dämonen und andere böse Wesen in den koptischen magischen Papyri“).

This lecture focused on the popular demonology of late antique Egypt (ca. 400–1200 CE) as revealed by Coptic magical texts, written in Coptic, the final stage of the Egyptian language, and illustrating a primarily Christian worldview, but one strongly influenced by its Egyptian setting and the Greco-Roman and later Islamic cultures that dominated Egypt at the time. The talk was structured around four questions: where did demons come from? What subclasses of demons do we find in Coptic magical texts? What did demons look like? And how did human beings interact with them in the context of magic?

As is common in orthodox Christianity, demons in Coptic texts are seen primarily as fallen angels, led astray by the Devil. While this idea originated in Hellenistic Judaism, a particularly rich account of the demonic fall is found in the Coptic Investiture of Michael, which describes how Mastema the Devil was once Saklataboth, the first-created being and the commander of the heavenly armies, but fell when his pride would not allow him to bow down before Adam, the human being created in the form and likeness of God. The angels who fell with him became the demons, the evil spirits who filled the earth and air, provoking sin and suffering among humans.

The basic vocabulary of Coptic demonology is drawn from the Greek-language Bible – daimōn or daimonion (‘demon’) and ‘spirit’ (pneuma), often specified as ‘unclean’ (akatharton) or ‘evil’ (ponēron), but a subcategory of demons take the names of “pagan” gods, interpreted in Judaism and early Christianity as demons who had tricked pagans into worshipping them. Greek deities such as Zeus and Apollo are listed alongside demonic names, and the plural of the native Egyptian word ‘gods’ (ntēr) shifted meaning to become a type of demon.

Alongside occasional mentions of beings drawn from Arab folklore, such as the djinn, we also find mention of one instantiation of the pan-Mediterranean and West Asian child-killing demoness, who appears in other traditions as Lilith, Lamia, Gyllou, or Al. In Coptic, her name is Aberselia, apparently from the Aramaic parzela (‘iron’). There was almost certainly a narrative prayer against Aberselia in Coptic, but it only survives in Ethiopic, in which Aberselia’s name is written as Werzelya. In this text her enemy is Saint Sisinnios, a Christianised form of the ancient Semitic heroic figure of Sassam bar Purāduš, who appears in the Greek magical corpus as Sesengen Bar Pharanges.

Finally, another subcategory of malign being is constituted by the dark angels responsible for tearing the souls of sinners from their bodies and torturing them in hell, known by numerous names, including ‘Powers of Darkness’ and ‘Decans’ (a name originating in Graeco-Egyptian astrology). These are one of the rare categories to be described in detail: literary texts depict them as dark figures, often drawing upon Egyptian religious iconography to depict them as animal-headed monsters.