Fellowship Report

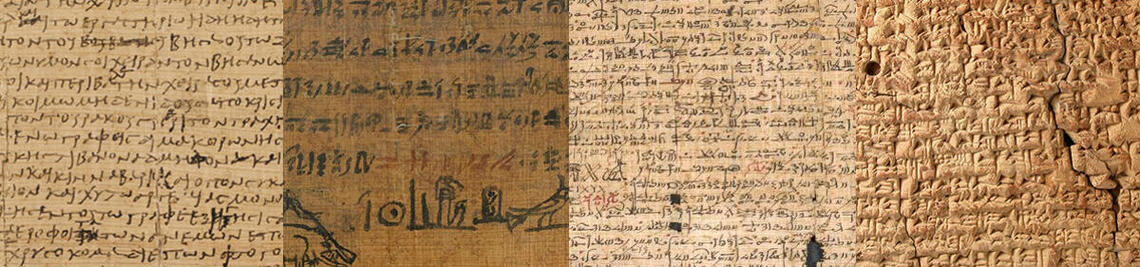

As a component of my FWO-funded postdoctoral research at KU Leuven, I had the privilege of being a junior fellow at the MagEIA project in Würzburg during May and June of this year. My three-year project looks at how priestly communities in the late first millennium BCE copied and composed prayer, with a focus on three blocks of material: the book of Psalms, Jewish communities in Persian Egypt, and the priestly archives of Late Babylonian (LB) Uruk. Texts related to recitative literature (e.g., magic, ritual, and prayer) are all products of human writers, and these texts were part of a cultural system that extended beyond the contents of the tablets. These three examples provide spaces to ask questions about how priestly communities which have lost political independence and power relate to the inherited texts of their past, and how those communities can negotiate their new standing in society through prayer, magic, and ritual. While at MagEIA, I worked on the Uruk component of this project, where I made good use of the well-stocked ancient Near Eastern library at the Residenz, and where I could draw on the expertise in Assyriology available in the faculty at Würzburg and at MagEIA.

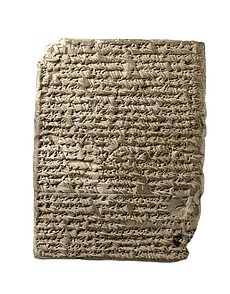

I presented the result of my research here at two events on June 11th. First, in the morning, I presented the text TU 58 (AO 6489), an Aramaic incantation written in syllabic cuneiform. This text is not a translation of a known Akkadian or Sumerian original, even as it draws on imagery and formulations which are available in those incantation traditions. More importantly, it signifies the complex nature of LB Uruk, where different languages and traditions were interacting. This is especially valuable considering that our evidence is heavily tilted towards cuneiform writing, with hardly any preserved Aramaic texts. That the incantation stands at the intersection of several different academic disciplines made it an excellent subject of discussion at MagEIA. Sitting between Akkadian magical practices and later Aramaic traditions from Mesopotamia (including Jewish ones!), any examination of this tablet requires cooperation between these different specializations. The text provided the space for a fruitful discussion on the backgrounds and afterlives of the various elements of the incantation.

Later in that afternoon, I presented a lecture on how the prayers collected and composed by the priests at LB Uruk relate to the political, religious, and social changes of their time. The collection of prayers and incantations found in the archives of the main temple, the bīt rēš, and those found in the nearby archive of the exorcists provided the material to investigate. Though there is a high degree of continuity with texts in earlier periods, the archive here is distinctly Urukean. Archives are always the product of choices, whether or not they are intended. Some of these prayers and incantations reflected the renewed interest at Uruk in the deity Anu, others reflected the developing interest in celestial sciences, and others (like the Aramaic tablet, TU 58) show departures from the long tradition of Mesopotamian magic and prayer. In the types of texts they choose to copy and create, these priests had agency, and the effect was to inform and even create a public who would be especially receptive to these new conceptions of Urukean religion.

I want to thank the principal investigators of this project, Prof. Dr. Daniel Schwemer, Prof. Dr. Daniel Kölligan, Prof. Dr. Martin Stadler for hosting me during this time, and for the rest of the fellows and the staff for their warm and generous welcome. My stay in Würzburg proved to be incredibly productive, and my conversations and interactions with everyone have had an important impact on the direction and results of my research.