Multispecies Storytelling

In the winter term 2025/26, Fernanda Haskel, a scholarship holder within the program in Psychosociology of Communities and Social Ecology at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Brazil, worked together with our group. The story of a gardener about the comforting power of St. John’s wort inspired Fernanda. Forming a novel plant story, she connected the luminosity of the medicinal plant with the history of her family that had migrated from Germany to Brazil in the nineteenth century.

THE DREAM OF THE FLOWER

By Fernanda Haskel with Johanniskraut

This is the story of a plant that dreams at the edge of a flower bed.

It dreams and makes others dream. Dreams are ancestral technologies[1].

The plant and its people dream to navigate between worlds.

In a town littered with concrete buildings, a woman slumbers.

After hearing its name for the first time, St. John’s Wort infiltrates her dreams. It germinates a dream-memory about a blue balloon flying over a land without civilization.

When the woman awakens, the flower’s German name blossoms in her heart: Johanniskraut (St. John's Wort).

Enchantments are the plant’s pedagogy.

Johanniskraut uses its witchcraft to bewitch and adopt the woman.

It cares for and guides her. It is a magical plant that helps overcome losses.

Surrendering to Johanniskraut’s spells, the woman’s dreams become dreams of flowers. She sows and is sown by Johanniskraut.

Together, they cultivate gardens of memory and memories of gardens.

Her skin is pollinated by the pollen of the flower's sunny petals.

Sap and blood merge. Tangled roots penetrate her body.

Her body is no longer hers alone; it has become territory shared with the plant she is falling in love with.

St. John’s Wort occupies her whole being, and she allows herself to be occupied by other ways of living.

Hypnotized, she is transformed into a body-territory where dreams sprout from the earth.

Love is the meeting ground, the commonality of their existences within their differences.

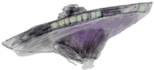

In the middle of castles and churches, bells and sirens, Johanniskraut blooms at the summer solstice. The flower dreams of the sun at its zenith. That is why it shines like the sun itself, its golden filaments like rays of sunlight bringing light into the darkness.

Navigating between worlds, St. John's Wort lives on the border between medical and magical use—at the crossroads of superstition and science, in the folds between laboratory and legend[2].

Healing women once recognized Johanniskraut as a sorceress plant, a wise healer, and sometimes knew it as Mary’s Blood Herb or Witch’s Herb.

They used it in spells and remedies. Many of these women were later labelled “witches” by patriarchal and colonial structures. Ironically, subsequent records suggested using the herb to guard against witches.

It was said that the holes in Johanniskraut’s leaves were made by the devil, angry at the plant’s protective powers[3]. Science, in its turn, revealed that its leaves have translucent vegetative glands where medicinal properties are concentrated. St John's wort is helpful for depression, and the plant was soon turned into a packaged supplement on supermarket shelves.

What would the leaves say? Plants do not have the habit of drawing words on paper skin like civilization does[4]; instead, Johanniskraut records its experiences in fragmented images captured by the holes in its leaves that allow sunlight to shine through.

It carries the memories of the sun touching the earth.

The woman, who talks to the last flower of the summer, notices that Johanniskaut is a specialist of a grammar of care and a writing of affections.

The translucent spots in the St. John's leaves are open pores of a trans[5] skin. They are mechanisms for changing our way of perceiving, for trans-see worlds: “The eyes see, memory reviews, and imagination ‘trans-sees’.”[6]

Experts in plant literature have said that the leaves reveal cryptographic poetry or a kind of musical score[7].

Sol in light, sound, and tone.

What men see as light, the plant people feel as sound.

As the wind passes through their leaves, it whistles the plant’s musical scores into Zauberworte whispers (enchanting words).

Man perceives St. John’s Wort as a plant. But it sees itself as human[8] with flower skin and dressing perforated leaves.

Between reason and madness[9] , the leaves tell a story of care, magic and connection. Johanniskraut’s flowers are disobedient and insistent on life.

They do not yield to control.

They open cracks in the norms, break the order, and dissolve the concrete. Plants live with no designated place to bloom.

By dreaming with the sun, Johanniskraut asks:

What worlds can be born when we listen to what blooms at the edges of flower beds? At the edges of the worlds? At the edges of so-called civilization?

Navigating between worlds, St. John’s Wort teaches us to dream at the edges of flower beds.[10]

By Fernanda Haskel with Johanniskraut

Translation revised by and adapted with Laura Dolan

[1] See The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman, Bruce Albert and Davi Kopenawa.

This story was written with Speculative Fabulation (Anna Tsing, Donna Haraway, Vinciane Despret).

[2] Neurobiological studies show that St. John's Wort has positive effects in the treatment of depression, degenerative brain diseases, cases of dementia, and hormonal changes, such as PMS and menopause. Even after mapping its biochemical interactions and decoding its properties and components, the mechanisms of action of St. John's Wort are not fully understood. In folklore, it is said that the plant wards off witches and evil spirits that agitate and disturb the mind.

[3] That's why they are known as Hypericum Perforatum — perforated in Latin. These holes show who Das Echte Johanniskraut is — the true St. John's Wort, in German.

[4] See The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman, Bruce Albert and Davi Kopenawa.

[5] “Trans” as in “the other side of.” In this case, devices for crossing over to the trans-lucid ways of reasoning. The windows of language, magical doors of passage between worlds.

[6] Manoel de Barros (1996), a Brazilian poet.

[7] Plant literature is a branch of Therolinguistics, a science invented to study savage language and politics (Ursula k. Le Guin; Donna Haraway; Vinciane Despret).

[8] Perspectivism and Amerindian Thought (Viveiros de Castro and Brazilian indigenous peoples, such as the Guarani, Krenak, and Yanomami). This refers to the ontological twist of world construction in relation to others who see themselves as human and do not see us as humans, but rather as wearing different clothing (bodies). The partnership with plants in this writing comes from the recognition that they are people.

[9] See Michel Foucault and his studies on power relations, reason, and madness.

[10] This work is supported by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES) - Funding Code 001, essential for undertaking the study abroad period, according to the Sandwich Doctorate Abroad Program (PDSE)

At the beginning of the new millennium an originally mediterranean wildbee appeared in the South of Germany: the Violet Carpenter Bee. |  |

In Franconia the bee was initially attacked as a dangerous stranger (interpreted as Ufos).

Twenty years later, the bee has been accepted as important Co-gardener.

In 2022, the Violet Carpenter Bee was elected as animal of the garden (Heinz-Sielmann-Stiftung), in 2024 it was elected as wildbee of the year. |

More and more gardeners are accepting the needs of the Violet Carpenter Bee: Dead apple trees are allowed to remain in the garden, salvia enforces the mediterranean communities of plants.

Reinforced by climate change the Violet Carpenter Bee also migrates to Northern Europe. Like many other species, the Violet Carpenter Bee is here to stay. |  |

Idea: Prof. Dr. Michaela Fenske

- Mit der Blauen Holzbiene Denken. Neue Perspektiven auf die Verflechtungen von Menschen und Insekten. In: Bayerisches Jahrbuch 2023.

- Becoming Aware of Insects: Dangers and Endangerments in the Anthropocene. In: Hollsten, Laura et al. (ed.): Human-Bug Encounters in Multispecies Networks. Boston/Leiden 2025.

Design: Dr. Sandra Eckardt